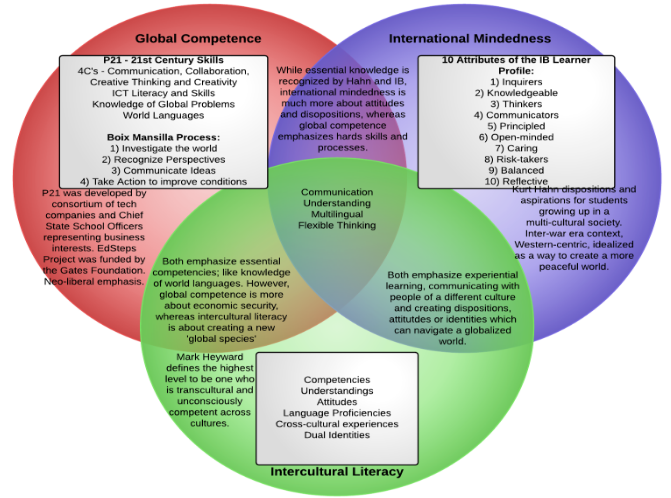

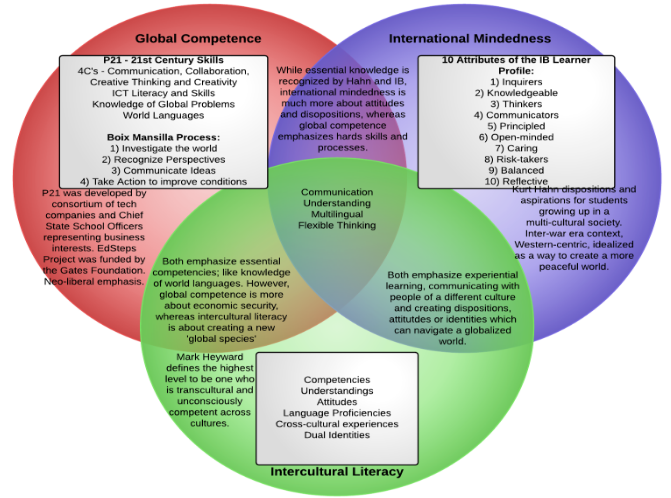

Mark Heyward defines Intercultural Literacy as the unconscious, transcultural ability to empathize with another from a different culture, to take on their perspective and embed it into your own thinking, to be the dynamic, multilingual ‘mediating person’ who can navigate between and among many different kinds of people.

For Heyward there are many reasons to aspire to this high level of cultural competency; to make the world more cooperative, safer, and sustainable for all, while also ensuring each person’s economic competitiveness in a globalized world. It is not clear where his emphasis lies, but the economic security of being interculturally literate is not mentioned first and is not mentioned repeatedly in his paper From international to intercultural. In fact, Heyward is setting a very high aspirational goal for a new ‘global species’ of human who still occupies a plurality of identities, but has gone well beyond a nationalist or monolingual culture and identity and has instead become transcultural.

Of course, Heyward argues that international schools are uniquely positioned to provide the environment which shepards young students through their ‘crisis of engagement’ and onto progressively higher levels of mono-, cross- and intercultural literacy. This ‘crisis of engagement’ as Heyward calls it, is essential, for only through experience and encounter with the other can one begin to understand and then move on to integrate the other cultural and social imaginary. This eventual unconscious integration of bicultural and transcultural identity is problematic in a world that is in many regions and nations backlashing against notions of transnational economic cooperation and transnational pluralistic societies. Looking at the white nationalist movements in the US and Eastern Europe as an extreme, one can easily assume the virulent objections concerning the loss of culture, identity, and the dangers of a monocultural or multicultural society that would be raised. There are more legitimate concerns, of course, like those who would see this transcultural process as another form of cultural imperialism from the west, or those developing nations that use a national image and identity to spur growth and energy in its workforce.

Intercultural literacy shares an emphasis on experience as a philosophical footing with international mindedness (IM). The term IM is associated with Kurt Hahn and the International Baccalaureate programmes (IB), and the experiences are meant to engender the dispositions and attributes of an IB Learner; risk-takers, caring, principled, open minded and more.

Dr. Arathi Sripakash and his colleagues, in their study of six IB schools in Australia, China and India, found a significant association with IM and Hahn’s idealized traditional western education and the IB World Schools acknowledgement that they come from a humanist western tradition. In fact, many students and families enrolled in IB schools in these countries see IM as a form of “western cultural capital” intended to help them navigate the western higher education system. The study found that IM in these schools and cultures was more curriculum and instruction focused and put less emphasis on the constructivist or experiential learning that both Hahn and Heyward find essential to creating a student who can effectively navigate and contribute to a globalized world. Thus, Sripakash describes a very practical version of IM which is limited in its effect on student identities and does deeply engage students in the tensions between the nationalist project of developing China, say, and the international education pursuits of its highest achieving students.

In this practical vein, we move on to global competence, as defined by Veronica Boix Mansilla and Anthony Jackson in the Asia Society’s joint publication with the Council of Chief State Schools Officers (CCSSO) entitled Educating for Global Competence. In it, Mansilla and Jackson define global competence as “the capacity and disposition to understand and act on issues of global significance.” Action to “improve conditions” in the world is emphasized throughout the document, but most especially in the matrices for global competence in multiple subject areas. To build global competence in students all subject area teachers should follow the following learning cycle:

- Investigate the world

- Recognize perspectives, both their own and others’

- Communicate ideas, to diverse audiences

- Take action, to improve conditions

The notable verbs repeated in all the subject area matrices are the following: Identify, Analyze, Produce, Recognize, Examine, Explain, Explore, Use, Select, Reflect, Assess, Act

Aside from ‘reflect’, this comes off as a very western-oriented actionable matrix. Even in the global competence matrix for the world languages subject area it is all about the functionality of the second language. For example, “reflect on how proficiency in more than one language contributes to their own capacity to advocate for and contribute to improvement locally, regionally or globally.” This is all about the ability to “improve conditions”, not about the reflecting upon new awarenesses, interconnections made, perspectives newly understood and adopted, not much at the intercultural literacy level advocated by Heyward.

In fact, there is a whole body of western imperialism criticism of international education, and particularly the international mindedness of the IB programmes, being the most prominent and common model of international schools worldwide. Lodewijck van Oord argues that there are three primary western liberal epistemological assumptions embedded in the IB Diploma Programme:

- Marketplace of ideas, wide range of valid opinions

- Questioning is central, fallibility is acknowledged

- Marketplace of ideas will lead to truth, the best ideas win out

Citing Blooms and Gardner, van Oord makes the case that our traditional western liberal values tell us that mean-making is the ideal end of education, and that conceptual knowledge has primacy over rote learning of quantities of content.

In addition, Barry Drake takes van Oord’s conclusions about the values found in western liberal education and how the IB programme reflects those values, and calls on education policy makers in non-Western, non-Eurocentric nations to deeply consider the implications and potential ‘cultural dissonances’ produced when those Eastern, African or Latin American nations adopt the IB programmes in their national schools. In terms of teaching methodology

the PYP is committed, unapologetically, to “. . . structured, purposeful inquiry, which engages students actively in their own learning, because it is believed that this is the way in which students learn best. The PYP believes that students should be invited to investigate important subject matter by formulating their own questions, looking at the various means available to answer the questions and proceeding with research, experimentation, observation and other means that will lead them to their own responses to the issues.” This is the IBO basically declaring a constructivist theory of learning. Meaning making through first person experience, which is a western pedagogical approach and yet also problematic in the west with western students in some settings, high poverty and trauma communities. Thus, the adoption of this epistemology and pedagogy must be done intentionally, Drake argues, so that the environment for cross-cultural cultivation is set appropriately.

My philosophical beliefs in how children be taught and should learn definitely fall into the western liberal tradition. I believe in meaning making through inquiry and that truth will reveal itself in the marketplace of ideas. But I certainly acknowledge that these assumptions are fraught, or simply ineffectual, for many communities and cultures. Like I said, constructivist learning does not work for all students coming from the western tradition, direct instruction, rote memorization and deep content knowledge are aspects of teaching and learning that are important even in the western education setting and indeed work better for some students, particularly those coming from high poverty or trauma situations where uncertainty in learning is not desirable. The pitfalls for non-western students can be even greater, identity alienation and a lack of relevance and reflection of their own lives in the educational setting. That lack of practical connection between their own lives and traditions and the learning taking place in their school, is the opposite intent of the western tradition of educating, thus it can self-defeating.

That being said, there are value judgments made when deciding upon education policy, and in curriculum and instruction choices, and I would tend to the integration of IM, IL and GC into a school curricula because I see the need for a trained, culturally competent citizenry in a globalized world, I’ve experienced the joy of intercultural experience, and those ‘crisis of engagement’ have been the most important formative experiences of my life and continued education. I agree with Drake, that it is critical for policy makers, school directors and teachers to consider the effect and implications for adopting IM through the IB programmes in a non-western school setting, but that does not mean that the right environment, the appropriate considerations, and the positive, identity affirming experiences cannot be achieved in the name of higher order thinking strategies, meaning making and self-actualizing student imaginaries.

Sources:

Heyward, M. (2002). From international to intercultural: Redefining the international school for a globalized world. Journal of Research in International Education,1, 9-32. Retrieved February 16, 2018

Sriprakash, A. (2014). A comparative study of international mindedness in the IB Diploma Programme in Australia, China and India(Publication).

Boix Mansilla, V., & Jackson, A. (2011). Educating for Global Competence: Preparing our Youth to Engage the World(Rep.). New York, NY: Asia Society.

Lodewijk van Oord (2007) To westernize the nations? An analysis of thevInternational Baccalaureate’s philosophy of education, Cambridge Journal of Education, 37:3, 375-390, DOI: 10.1080/03057640701546680

Drake, B. (2015). International education and IB programmes. Journal of Research in International Education,3, 189-205. Retrieved February 16, 2018.